When Danielle Nicklas started her third year in her Ph.D. program in pathobiology, she chose a project channeling her own frustrations with the quality of menstruation options while studying abroad. Seeing the potential for reusable and environmentally friendly menstrual products, she collaborated with others in a medical entrepreneurship course to create NovvaCup, a sustainable solution to tackle challenges women encounter in menstrual care, especially in the wilderness, or areas with limited facilities. NovvaCup views its mission as a social enterprise, advocating for menstrual health education and inclusivity. Their work which applies clinical medicine, biomedical engineering and science to solve a problem all women face, also aims to destigmatize discussions around menstruation and create a more welcoming environment.

Danielle is one of a growing cadre of female inventors at Johns Hopkins who are channeling their entrepreneurial energies to design products for women. This momentum tracks with the broader growth in “femtech,” a specialized technology sector focused on serving women’s distinct health care needs. According to Straits Research, the global femtech market will grow from $45B to $140B by 2031, at a CAGR of 13 percent.

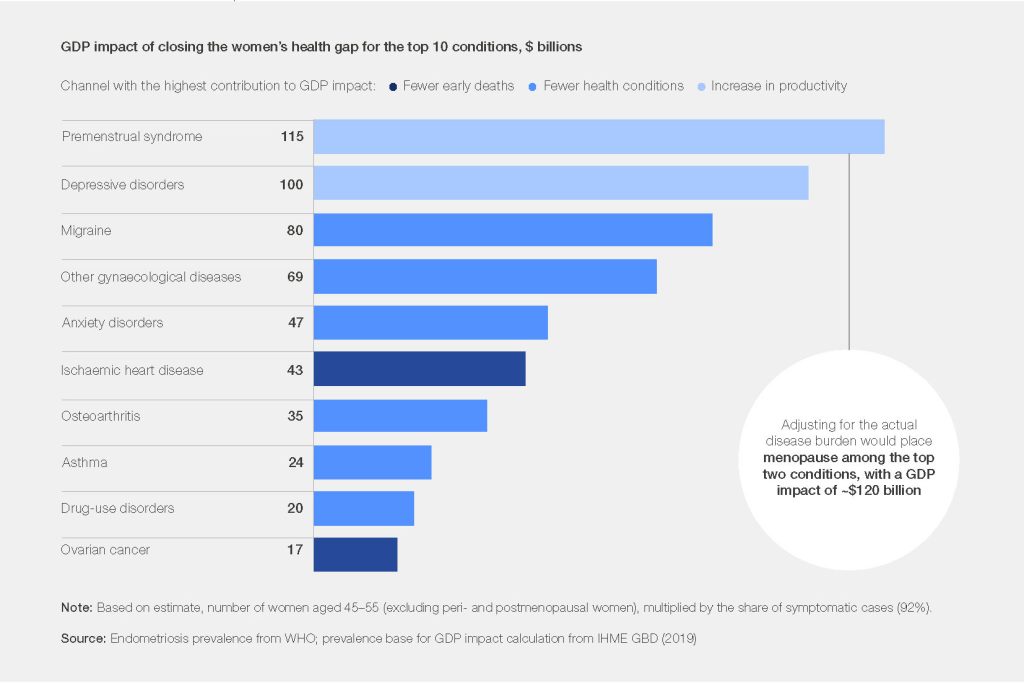

The argument for increased investment in women’s health and well-being takes several forms, chief among them an economic argument. According to a report from the World Economic Forum and the McKinsey Health Institute, Closing the Women’s Health Gap: A $1 Trillion Opportunity to Improve Lives and Economies, closing the gender health gap could inject $1 trillion into the global economy by 2040, benefiting billions of women worldwide with an estimated seven extra healthy days per year, translating to around 500 days over a lifetime. Each dollar invested in women’s health could yield about three dollars in economic growth.

How closing the women’s health gap could boost GDP.

Image: Courtesy WEF

The health care system has drawn attention for its failure to support women. Perhaps most glaring is a fifteen-year gap in data on drug efficacy/safety for women. In 1977, the FDA recommended excluding women of childbearing age from drug trials. Until this guidance was rescinded 1993, trials relied solely on data from men. Since then, research funding for women’s health and private sector investment has continued to lag, amounting to a systematic failure that perpetuates disparities in diagnosis, treatment, and access to care.

Enter “femtech.” The term entered the popular lexicon in 2013, when Ida Tin, the Danish co-founder of Clue (a menstrual cycle tracker currently with 10 million monthly users) began to use the term. Tin’s stated goal was to take female reproductive health “out of taboo land” and to start a “reproductive health revolution.” Defined as technology designed to address the unique needs of women across many health sectors, the current trends in femtech fall into several broad categories: fertility automation, period pain management, gynecological health, menopause management, precision oncology, and advanced maternal care.

Among those filling this void at Johns Hopkins is Efie Kokkoli, Ph.D., a researcher at the Johns Hopkins Institute for NanoBioTechnology. Dr. Kokkoli’s research is aimed at revolutionizing treatment for triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). Treating TNBC presents significant challenges due to its aggressiveness and resistance to existing treatments. Dr. Kokkoli’s research involves using tiny particles to deliver genes and drugs to treat cancer by targeting cancer cells specifically, while sparing healthy ones. They can also react to changes in temperature or acidity in the body. Additionally, her team creates special gels that can dissolve in the body and release drugs in specific areas, near tumors, or be used to grow cells in the lab for studying cancer.

A passion for women’s health is prevalent among Johns Hopkins students participating in our FastForward U student entrepreneurship program. Take Selena Shirkin, a biomedical engineering student at the Whiting School of Engineering. Selena is tackling emergency in-utero surgery, a risky procedure performed on 120,000 babies in the United States each year. Membrane rupture occurs in 30% to 40% of cases. Shirkin led a team to design a safer solution, focusing on preventing membrane rupture. Their research revealed that the main cause of rupture is the use of inappropriate surgical devices. To help address this, and in collaboration with experts, they developed a novel port system designed for fetal therapy, which is currently in the prototype stage. Shirkin aims to take this project beyond the classroom, believing it has the potential to make a significant impact.

As the innovator community at Johns Hopkins develops new ‘femtech’ solutions, the institution is also investing in the policy aspects of women’s health. At the Bloomberg School of Public Health, a new Center for Global Women’s Health and Gender Equity will address pressing issues affecting women and girls worldwide. It aims to unite stakeholders globally and within Johns Hopkins to advance gender equity through applied research, training, and mentoring. The Center’s initiatives include a scholars program, the Evidence Accelerator cohort, to cultivate future leaders in applied gender equity.

The femtech sector has experienced marked growth in the past several years, valued at more than $59 billion in 2023, with projections suggesting overall value will reach $103 billion by 2030. One of the biggest drivers of femtech is the increase in prevalence of women as investors. Venture capital funds of note include BBG Ventures (Built By Girls), which recently closed a $50 million fund, the Female Founders Fund, Forerunner Ventures, Halogen Ventures, SoGal Ventures, Serena Ventures (Serena Williams), and Pivotal Ventures (Melinda Gates). In the past decade, the number of firms dedicated to funding female founders, many of which focus on women’s health, has surged.

While the underrepresentation of women as founders, investors, and inspiration for innovation continues to plague the tech industry, femtech’s future looks bright. As we gain deeper insights into the unmet needs of women’s health, and as more women from Johns Hopkins direct their efforts towards entrepreneurship to address these challenges, more progress towards equity is on the horizon.

Are you inspired by a Johns Hopkins female inventor? Recognize them here as part of our Women in Innovation community.