As vice chair of research for the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine at Johns Hopkins, Sujatha Kannan frequently checks in with her colleagues about their work. When she asks men about possibly commercializing their research, it most likely has crossed their minds or at least been mentioned by someone else, she says. That is not the case with female colleagues.

“Typically when I talk to women, they haven’t thought about it because no one has brought it up to them,” says Kannan, who also is a professor of anesthesiology and critical care medicine and pediatrics.

Kannan is trying to change that one conversation at a time and leading by example. She has turned her research on imaging and targeted therapy for pediatric brain disorders using nanotechnology into Ashvattha Therapeutics, which wants to treat a variety of diseases by selectively targeting cells associated with inflammation.

Kannan’s entrepreneurial role is unusual at Johns Hopkins, where women make up about 44% of the faculty but only 11% of startup founders. But Johns Hopkins is not alone: Fewer than 10% of startups at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology were founded by women, who make up 22% of the faculty, while 11% of Stanford University startups had a female founder despite 25% of faculty being women.

Female researchers often want to focus on their research and patients instead of commercialization, Kannan says, or worry about conflicts between research and a potential business. Kannan admits she had these concerns before becoming an entrepreneur, too, and wants to help colleagues overcome them.

“I have learned that unless we are heavily involved in the business aspect of our research, our ultimate goal — to reach the most people as possible — will not get realized,” she says.

For Kannan, that meant founding a company that aims to treat people with a variety of ailments instead of just helping them live comfortably. She particularly wanted to help children born with neurological disorders such as cerebral palsy, autism and meningitis, the latter of which can be fatal.

“Intuitively, one would think that when you’re young and get an injury, your brain is still growing so you should really be able to make new circuits because the brain is not completely developed yet,” she says. “But we don’t often see that. In fact, people think that if you have an injury before birth or during birth, you can never recover from it.”

With her husband, Kannan Rangaramanujam, a professor of ophthalmology and co-director of the Center for Nanomedicine at the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins, she developed a type of squishy ball-like molecule called a dendrimer that can deliver a drug directly to a cell while not affecting the surrounding area.

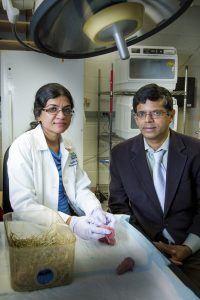

Sujatha Kannan and her husband, Kannan Rangaramanujam. (File photo)

The couple focused on neuroinflammation, which initially walls off an injured area to give immune cells time to repair, but if left unchecked can lead to a variety of ailments. If the inflammation can be stopped, they reasoned, the immune cells can get back to their regular work.

They started testing with N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), an over-the-counter supplement that has been tried unsuccessfully to treat a variety of neurological disorders. She injected dendrimers with NAC into newborn rabbits born with cerebral palsy. By the time the rabbits were 2 months old, they looked and walked like healthy rabbits.

Johns Hopkins recruited the couple in 2011, and they expanded their research by working with 30 labs around campus. It was only after they were “100% sure” of their research that they formed Ashvattha, where Kannan sits on the board with her husband, who also serves as chief technology officer.

Since the dendrimers can transport any kind of drug, Kannan says Johns Hopkins Technology Ventures helped the company file broad patents for the technology. Ashvattha hopes to do testing in humans in the next few years and is in the midst of raising funding.

The company also hopes to spin off companies that use the technology for specific areas, as it already has done for neurology (Orpheris) and ophthalmology (RiniSight). The name Ashvattha comes from the Sanskrit word for the eternal fig tree under which Buddha meditated that keeps regenerating its roots.

And Kannan will make sure the company addresses pediatrics, the reason she became an entrepreneur in the first place.

“The most important thing is that you just have to be excited about the research you are doing, and think really big about who are all the people you can help with the drug or device,” she says when asked what advice she would give aspiring entrepreneurs, men or women. “If everything works, who are all the people who would benefit from it? If you keep that as the big goal, everything else, all the small ups and downs, really don’t matter because the goal remains the same.”