The following was originally published in The Hub.

The summer before starting his Johns Hopkins career, first-year student Saardhak Bhrugubanda received an email from one of his future classmates. Sophomore Jerry Zhang was designing a new surgical mask for an undergraduate competition, and he needed help.

Bhrugubanda, who had worked on computer-aided design for his high school robotics team, leaped at the opportunity to work with his fellow engineers during a remote semester when extracurricular opportunities would be hard to come by.

“I knew going in that everything was going to be through Zoom this semester, so this seemed like a great chance to learn and grow outside of the classroom, and hopefully make a few friends as well,” Bhrugubanda said.

Together with Zhang, Bhrugubanda and 22 other students formed the design startup Polair and set to work on creating a surgical mask of the future. They were awarded $250,000 from industry leaders last month for their clear, adjustable mask.

The XPRIZE competition challenges innovators around the world to imagine new solutions to challenges in fields such as space, education, health, energy, and the environment. The organization’s Next Gen Mask Challenge invites young innovators between the ages of 15 and 24 to develop prototypes that improve on current face masks. Hopkins’ Polair team took home the Future Forward award, which recognizes prototypes that reflect the future of mask technology.

The Polair design features a magnetically attaching modular mask with customizable front attachments, allowing for total flexibility among users. According to Zhang, a biomedical engineering major who served as the team captain, Polair’s mask addresses three main weaknesses in current surgical mask technology. First, the flexible design of the Polair mask creates a firmer seal between the mask and face, cutting down on air escaping the mask, preventing glasses fog and germ transmission. Second, the mask has a soft silicone frame for increased comfort. Finally, the customizable front attachments include a clear, anti-fogging design for patient accessibility.

With 24 engineers making up the team, Zhang, who said he had long been interested in the opportunities afforded by the XPRIZE competition, split Polair into three groups, with each group tasked with solving one of the main issues they saw with current surgical mask technology. After a few weeks, the three teams brought their ideas forward and, as a group, combined the best concepts from each.

Rahul Swaminathan, a sophomore biomedical engineering major who worked on animations and modeling the mask, said the team’s size was a major factor in the quality of the final design.

“Our whole theme was adaptability, and because of our team, we were really able to attack the issue from a lot of different angles and play to our strengths,” Swaminathan said.

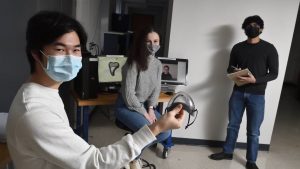

Polair team members (from left) Charles Wang, Gwyn Alexander, and Zan Chaudhry collaborate remotely with team captain Jerry Zhang (on computer screen). (Will Kirk/Johns Hopkins University)

Bhrugubanda worked with Swaminathan on CAD designs for the mask, and their teammates created prototypes with 3D printers. Together, he said, they were able to test theoretical problems with the design nearly instantly and make corrections in the digital file.

Bhrugubanda said the XPRIZE competition has been the highlight of his first year at Hopkins. Although the team had to work remotely owing to the pandemic, he said, they came together well under imperfect circumstances. The team was based in Baltimore, but its members worked remotely from three continents and 14 different states in the U.S.

Zhang said the team will use its funding to produce more professional prototypes and begin pursuing patents for their new technologies.

“[The XPRIZE competition] was a great start for Polair,” Zhang said. “We were able to get a nice experience working with professionals from Honeywell on how to best manufacture a mask, got some input on how exactly masks are designed and created, and are now positioned to take the next steps toward making these masks a reality.”

Though the team didn’t take home the $500,000 Grand Prize award, Bhrugubanda, said the team is thrilled about their placement in the competition and what it means for their product.

“It’s a prestigious award in my eyes,” Bhrugubanda said. “From an engineering perspective, we were named the mask of the future. That’s an exciting start to our journey with Polair.”