A Johns Hopkins startup is out to prove that unlimited, renewable and clean geothermal energy is readily available — right under most people’s feet.

Geothermal Technologies, Inc. (GTI) aims to harvest the energy found in hot sedimentary basins near Earth’s surface. Geothermal energy is typically associated with places known for volcanic activity (think New Zealand, Indonesia and Iceland), but hot sedimentary basins are found all over the world.

“The benefit to mankind is enormous,” says CEO J. Gary McDaniel. “If we can produce clean, baseload energy on a global scale, it’s a world-changer, not just a game-changer.”

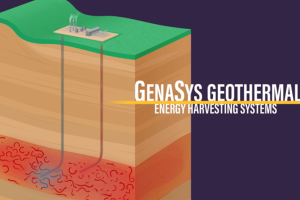

The idea is to use the water found in the aquifers of sedimentary basins to create a “big circulation system,” like a car’s radiator, says Bruce Marsh, the company’s chief scientific officer and a professor emeritus in the Morris K. Blaustein Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the Johns Hopkins University Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. Two wells are drilled into the basin. Hot water from the aquifer is pumped up one of the wells, and the heat from the water powers turbines and generators in the geothermal plant on the surface. The newly cooled water is then pumped down the other well, returning it to the aquifer, where it heats up again.

“We’re basically just renting the water,” says Marsh, a world-renowned geologist and expert on magma and volcanic systems.

How much water each system rents would depend on the electricity demand. GTI is making its system scalable, meaning its geothermal plants could range in size from “microgrids” — providing businesses and industry power where they need it — to large utilities.

Marsh came up with the idea of using hot sedimentary basins about a decade ago when a colleague was interested in looking into sustainable energy projects. Geothermal energy is produced around the world, but plants are limited to volcanic regions, making global availability impossible.

“I thought what we ought to do is go into areas where there’s already hot water, like in sedimentary basins, and build our own heat exchange system,” he says.

Subsequently, GTI developed proprietary technologies that help determine the best spots to drill, inform the design of the underground system, and monitor the system once in place. The company was able to develop its technologies, McDaniel notes, thanks to recent advances in drilling, seismic imaging and cloud computing.

“I think one of the reasons nobody’s done this before is because a lot of the technologies we’re employing didn’t exist 10 years ago,” he says.

The company, formed in 2018, licensed the technologies through Johns Hopkins Technology Ventures. JHTV, through its FastForward incubator, also introduced McDaniel to Marsh, who was going through the commercialization process for the first time.

“I was really happy to see how people do this,” says Marsh. “It was a real education for me, and Tech Ventures was a vital part of it.”

Brian Stansky, FastForward’s senior director, says GTI could be “one of the most impactful startups to emerge from our ecosystem.”

“It is a fascinating convergence of management expertise and technological advances that has the potential to solve a very large and critical unmet need for eco-friendly baseload power generation,” he says.

FastForward and JHTV work with technologies across sectors, Stansky added, and are looking forward to assisting with energy-related innovations that come from the Ralph O’Connor Sustainable Energy Institute, the university’s interdisciplinary home for ongoing research related to clean, renewable and sustainable energy technologies.

GTI now has a team of a dozen specialists, and the startup has raised $1.5 million so far, with plans to start raising another round of funding by the end of the year. It is collaborating with large corporations on all aspects of its system, McDaniel says, including Helmerich & Payne, the largest land-based drilling company in the United States; Halliburton, which is assisting with well completion and fiber optics; TechnipFMC, which is working on the wellhead design; and Sumitomo, which is assisting with metallurgy to determine the proper tubing for the wells.

GTI is working toward the construction of its first geothermal plant in eastern Colorado’s Denver-Julesburg basin. The drilling permit will be submitted by the end of September, with drilling starting early next year and plant construction completed by 2025, McDaniel says. By 2030, up to a dozen GTI-technology-based geothermal plants could be operational around the world, according to McDaniel.

“As Gary says, this could have a global influence,” says Marsh. “Johns Hopkins has made its name in the medical area in terms of combating and wiping out various diseases and developing first-rate surgical techniques. This, I think, is really within that category of impact.”