The following was originally published in The Hub.

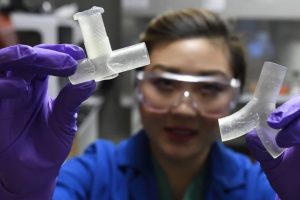

In response to a pressing need for more ventilators to treat critically ill COVID-19 patients, a team led by Johns Hopkins University engineers is developing and prototyping a 3D-printed splitter that will allow a single ventilator to treat multiple patients. Though medical professionals have expressed concerns about the safety and effectiveness of sharing ventilators, the team has designed this tool to address those concerns.

“There is an emphasis right now on using engineering to develop open-source solutions to many aspects of the COVID-19 crisis, but especially for ventilator design and production,” said Sung Hoon Kang, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at the Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering who is leading a team that includes ICU intensivists and pulmonary specialists at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. “One approach is to use one ventilator to treat multiple patients. While this is feasible, it must be safe for all the patients. That means ensuring that each patient gets the care they need, without shortchanging anyone. This is what we set out to create.”

A serious lung condition called acute respiratory distress syndrome, or ARDS, is the leading cause of death for COVID-19 patients. In individuals with ARDS, fluid builds up in the lungs, limiting the amount of oxygen in the bloodstream and depriving vital organs of the oxygen they need to function properly. The condition must be managed by a ventilator.

As the COVID-19 outbreak spreads, many health care facilities are grappling with a shortage of the machines needed to treat the sickest patients. Such shortages have already effectively crashed the health care system in Italy, which currently reports the world’s highest number of COVID-19-related fatalities at more than 13,000.

Some medical professionals have expressed concerns about the practice of sharing ventilators. First, hooking up several patients to the same ventilator could spread germs and create a chance for cross-contamination. Another concern is that a ventilator shared by multiple people wouldn’t give all of them the necessary level of oxygen, which could lead to poor patient outcomes and high mortality rates.

According to Kang, the team’s new design aims to safeguard against these risks. The new design includes an air-flow controller and flow meters, allowing clinicians to monitor and adjust air flow for each patient. The air volume controller is a key addition because each intubated patient requires different flow control. The team is also adding a filter designed to prevent cross-contamination between patients—important because early reports suggest that those exposed to multiple infected people experience worse outcomes.

The splitter also must be easy to deploy, given the urgency of the need.

“We need a robust design, but one that can be produced with a relatively simple manufacturing process like 3D printing,” says Christopher Shallal, a member of the team and a junior majoring in biomedical engineering. “We are also considering the different conditions and settings where people may be printing the ventilator splitters. For instance, they may not have a high-resolution printer available. So we are keeping scalability in mind as we design.”

Splitting ventilators is an experimental emergency treatment that has been used before under dire circumstances, such as during the aftermath of the 2017 Las Vegas shooting, when splitters were used to stabilize injured but otherwise healthy young adults. But splitting a ventilator to treat multiple patients in varying stages of lung failure presents a new and somewhat daunting set of design challenges, according to Julie Caffrey, assistant professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery at Johns Hopkins Medicine and a member of the team.

“Using the same ventilator settings for ARDS patients with different lung compliances could be very unsafe. One patient might receive too much air; the other might not receive enough,” Caffrey explains. “With ARDS, ventilator strategies for improving survival are often used to administer low tidal volume and higher pressure. If you can’t manage that, you risk causing further trauma to lungs that are already very crippled. It’s very important that when we split a ventilator, we can still set the ventilator to that specific patient.”

The team has produced the prototype and hopes to finalize and start testing their design on model lungs within weeks. Once approved by the FDA, they plan to publish their open-source design for others to use.

“The goal here is to quickly get this technology to hospitals around the world—and right to the people who need it the most,” says Helen Xun, a member of the team and a third-year medical student at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.