Written by Paul Nkansah, PhD

JHTV, Sr. Director, Corporate Partnerships

How the FDA’s April 2025 Decision Could Accelerate Biomedical Innovation, Adoption of AI, Organoids, and Other In-vitro Alternatives to Animal Testing and Usher in New Possibilities for Academic-Biopharma Partnerships

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently made a landmark decision to phase out mandatory animal testing for drug approvals, clearing the path for human-relevant alternatives and New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), including AI-based computational models, human cells, and organoid-based assays for toxicological testing.

As researchers transition away from animal testing, there remain open questions that only time will resolve. Will there be more risk for patients in Phase 1 studies? Will the biopharmaceutical industry accept this risk despite lessened requirements from the FDA? It remains to be seen whether modern in vitro and/or in silico testing can sufficiently capture drug properties such as toxicity or efficacy at the physiological level and properly de-risk Phase 1 drug candidates.

The hope is that the new FDA pathway will reduce the ethical burden of animal experimentation, lower research and development costs and ultimately drug prices, and accelerate the delivery of new therapies to patients, bypassing expensive animal toxicity testing.

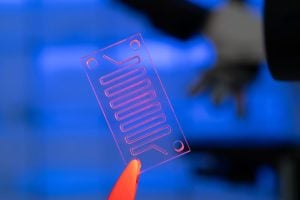

For decades, the FDA required animal testing as a prerequisite before any new drug or biologic, including monoclonal antibodies, could advance to human clinical trials. This requirement was rooted in the 1938 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, passed after a drug toxicity incident. Over time, however, growing ethical concerns, advancements in biotechnology, and mounting scientific evidence about the limited predictive value of animal models prompted change. In 2022, Congress passed the FDA Modernization Act 2.0, which officially allowed—but did not mandate—the use of non-animal methods like organ-on-chip technologies, computer modeling, and in vitro assays.

Rather than merely allowing non-animal alternatives, the FDA has now laid out a formal plan to phase out the requirement for animal testing, specifically for biologics like monoclonal antibodies. This includes setting up a framework to evaluate non-animal testing methods as primary tools for safety and efficacy assessment, signaling a more proactive stance. Crucially, it also aligns with updated FDA guidance for industry, which outlines clear regulatory pathways for developers to use validated alternatives.

This move acknowledges the growing body of evidence showing that certain non-animal methods can be more predictive of human responses than traditional animal tests. For biologics developers, it offers a more ethical, cost-effective, and potentially faster path to human trials. Importantly, it could accelerate drug innovation and approvals.

“The FDA’s decision to phase out animal testing is a significant step forward, said Lena Smirnova, PhD, who leads the microphysiological systems program at the Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing (CAAT). “By promoting NAMs and accepting in vitro and in silico data for investigational new drugs (INDs) submissions, the FDA is paving the way for more innovative and humane scientific practices. The MPS is also developing advanced in vitro models to better understand diseases like autism and improve drug screening processes.”

As the Director of CAAT at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Thomas Hartung, MD, PhD has led CAAT to become a global leader in advancing non-animal testing methods, including organ-on-chip systems, in vitro assays, and AI-based toxicology modeling. Hartung’s work has been instrumental in shaping scientific consensus around the limitations of traditional animal models and the potential of modern alternatives. The center not only conducts foundational research but also plays an influential role in policy and regulatory discussions worldwide.

“The industry does not need us academics for animal tests; they need us for the innovation,” said Dr Hartung. “We are making science fiction the technology of tomorrow.” He also noted that work with brain organoids will be critical, given that 25% of clinical trials are for brain diseases.

Together, academia and the biopharmaceutical industry can develop rigorous and scientifically sound strategies to support INDs in a way that aligns with the FDA’s evolving standards and ensures smooth pre-clinical to clinical development.